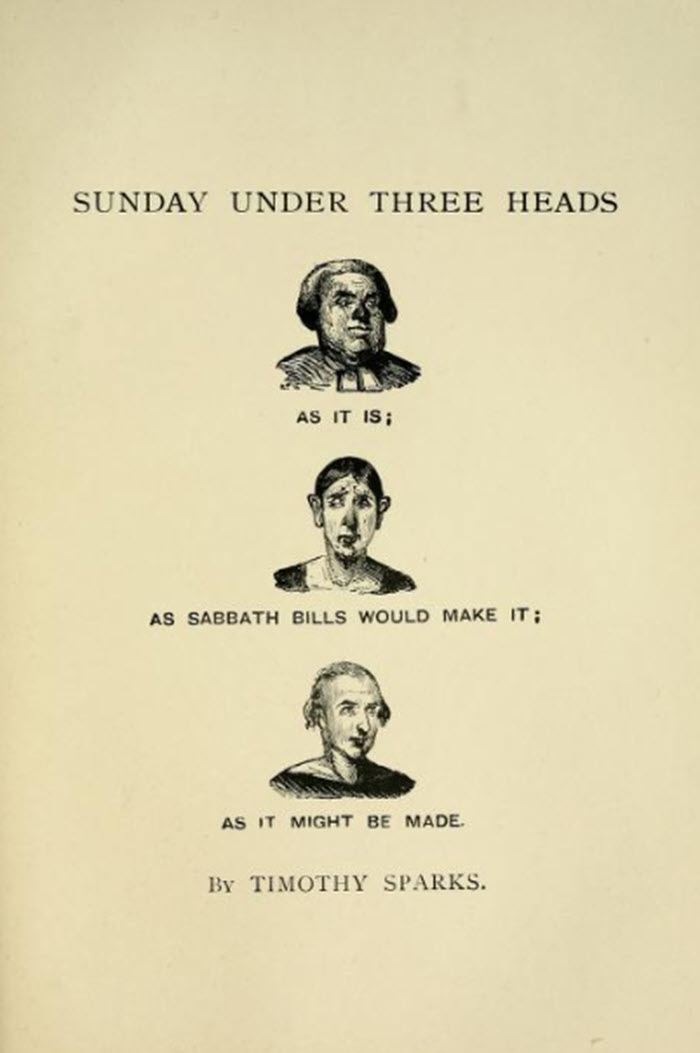

Sunday Under Three Heads is an early work by Charles Dickens published in 1836 under the pseudonym Timothy Sparks. The front cover was illustrated by Hablot Knight (known as Phiz), who would later go on to illustrate other works by Dickens.

At the time of its publication Dickens was about 22 years old and had just started on his journalistic career. He was not then well known as an author. He had already published the Pickwick Papers under another pseudonym, Boz, and this work had enjoyed commercial success, but Dickens had not yet established himself as a major literary figure or social commentator. He likely used a psudonym for Sunday Under Three Heads because of fear of backlash since it dealt with what was a controversial subject at the time.

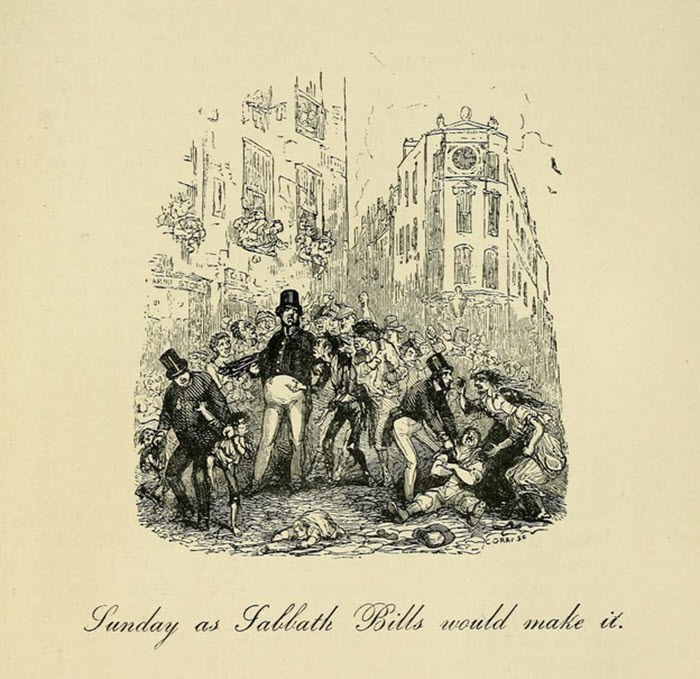

Sunday Under Three Heads is a short piece, no more than a pamphlet, arguing against a proposed law. The British Parliament, under the direction of an MP named Sir Andrew Agnew, 7th Baronet (21 March 1793 – 28 April 1849) was debating passing a so-called Sabbath law which would have outlawed all recreational and commercial activity on Sundays to promote Christian observance of the Sabbath. This controversy and worldview is alien to us, from the vantage point of a secular modern society in which there there are very little if any restrictions on what a person can on Sundays. It is perhaps difficult to understand Dickens' disgust at the proposed measure or how polarized Victorian society was at the time on this issue, but this was very much an iportant issue in Victorian Engliand.

Although the controversy which is the subject of this pamphlet as long since gone away, and Dickens' view prevailed, Sunday Under Three Heads is nevertheless an interesting work by Dickens because it allows us to see how Londoners lived and spent their leisure time during the Victorian era. It is essentially a time capsule and thanks to Dickens' prose and powers of description we can see this bygone world and the people who lived in it.

Dickens structures his essay into three sections, the so-called "heads" of the title. In the first session or head Dickens describes what Sundays in London are like now, then in the second section he describes the bleak conditions that would prevail if Lord Agnew got his way, and finally he sets out the idyllic way, Sunday could be observed.

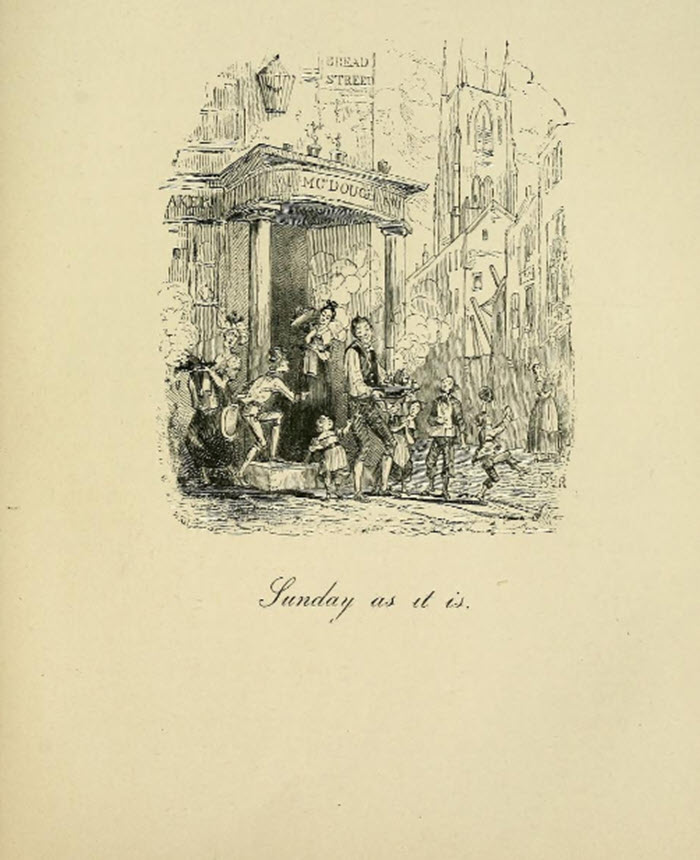

In this section Dickens describes how London currently spends its Sundays. He paints a happy picture of a contented populace heading out for outings into the country, or to the parks, or simply to run errands such as buying ingredients for Sunday dinner. The people are described as dressing in their finery, jostling and bustling in a happy throng of pedestrians, carriages, and riverboats. Here Dickens shines as an author describing daily life and the common people, and all the things that would be lost if the Sabbath laws passed.

Here is a quote from the Dickens' description of London life during that period:

Here and there, so early as six o'clock, a young man and woman in their best attire, may be seen hurrying along on their way to the house of some acquaintance, who is included in their scheme of pleasure for the day; from whence, after stopping to take "a bit of breakfast," they sally forth, accompanied by several old people, and a whole crowd of young ones, bearing large hand-baskets full of provisions, and Belcher handkerchiefs done up in bundles, with the neck of a bottle sticking out at the top, and closely-packed apples bulging out at the sides,-and away they hurry along the streets leading to the steam-packet wharfs, which are already plentifully sprinkled with parties bound for the same destination. Their good humour and delight know no bounds-for it is a delightful morning, all blue over head, and nothing like a cloud in the whole sky …

The afternoon is far advanced-the parks and public drives are crowded. Carriages, gigs, phaetons, stanhopes, and vehicles of every description, glide smoothly on. The promenades are filled with loungers on foot, and the road is thronged with loungers on horseback. Persons of every class are crowded together, here, in one dense mass. The plebeian, who takes his pleasure on no day but Sunday, jostles the patrician, who takes his, from year's end to year's end. You look in vain for any outward signs of profligacy or debauchery. You see nothing before you but a vast number of people, the denizens of a large and crowded city, in the needful and rational enjoyment of air and exercise.

Notably, Dickens' picture of Victorian London is happier, cleanlier and more prosperous than the polluted overcrowded city of slums and workhouses he depicts in Oliver Twist and other later novels. He does however acknowledge that there are poorer neighborhoods where the people lack the means to enjoy themselves as their more propserous neighbors, and he admits that "there is a darker side to this picture, on which, so far from its being any part of my purpose to conceal it, I wish to lay particular stress." There are some parts of London, Dickens acknowledges, where public drunkenness and lewed behavior is commonplace.

But, Dickens says, everyone has the right to a day of rest and recreation, and he wishes that the proponents of the law would understand what they would inflict on the common people:

I would to God, that the iron-hearted man who would deprive such people as these of their only pleasures, could feel the sinking of heart and soul, the wasting exhaustion of mind and body, the utter prostration of present strength and future hope, attendant upon that incessant toil which lasts from day to day, and from month to month; that toil which is too often protracted until the silence of midnight, and resumed with the first stir of morning. How marvellously would his ardent zeal for other men's souls, diminish after a short probation, and how enlightened and comprehensive would his views of the real object and meaning of the institution of the Sabbath become!

In this section Dickens lashes out at Lord Agnew and his supporters. He asks rhetorically:

It may be asked, what motives can actuate a man who has so little regard for the comfort of his fellow-beings, so little respect for their wants and necessities, and so distorted a notion of the beneficence of his Creator. I reply, an envious, heartless, ill-conditioned dislike to seeing those whom fortune has placed below him, cheerful and happy-an intolerant confidence in his own high worthiness before God, and a lofty impression of the demerits of others-pride, selfish pride, as inconsistent with the spirit of Christianity itself, as opposed to the example of its Founder upon earth.

He then goes on to describe the inevitable consequences of the Sabbath laws which would stifle any joy or pleasure that the people might have look forward to at the end of a long week of hard work. He describes the situation that would result in these terms:

Turn into the streets and mark the rigid gloom that reigns over everything around. The roads are empty, the fields are deserted, the houses of entertainment are closed. Groups of filthy and discontented-looking men, are idling about at the street corners, or sleeping in the sun; but there are no decently dressed people of the poorer class, passing to and fro.

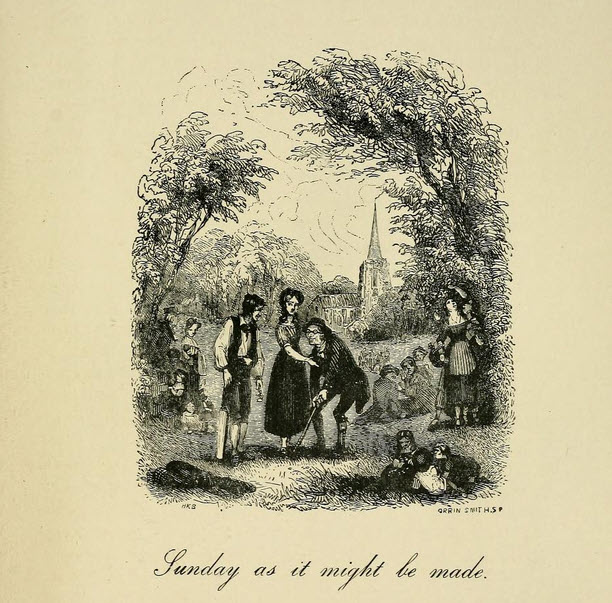

After describing the current pleasures of Sundays and contrasting them with the brutal theocratic regime that would be in place if Lord Agnew's bill passed, Dickens proposes his own reforms. He takes the view that religious feeling cannot be legislated or imposed, and that Sundays are made for man not God. He proposes a Sunday in which people are encouraged to festively participate in wholesome family sports, educational activities, and recreation. It is somewhat difficylt to understand the extent to which Dickens' version of the ideal Sunday differed from what he described as being currently in place except perhaps for its emphasis on getting exercise through family oriented sports and educational activities such as attending museums and galleries.

In 1836 a proposed law would have prohibited all leisure, recreational activities and shopping on Sundays.

Sunday Under Three Heads is a minor work by Charles Dickens which has not aged well. It was written to address a specific piece of legislation being debated in 1836, which ended up not being passed, and the controversy which gave rise to it has long since receded into the past. However, Sunday Under Three Heads is still an interesting time capsule showing what life in London was like during the early part of the 1800s, at the beginning of the Victorian era. It is also valuable as an example of Charles Dickens's early writing. We can see in it is later interest and preoccupation with social reform and the well-being of the lower and middle classes.

This article was written on March 30, 2021 and last updated on March 30, 2021.