Personal Life of Charles Dickens

Dickens' London

The following account is extracted from a book entitled "Home Life of Famous Authors" written in 1886 by

Hattie Tyng Griswold. Obviously this article is not the most up to date source of information on Dickens. There has been a lot of scholarship on the author since then. However, the fact that this essay was written not long after Dickens' death means that the author was able to gather together quotes and views from Dickens' contemporaries. It also offers a useful glimpse into how Dickens was regarded by those who knew him and during his own lifetime.

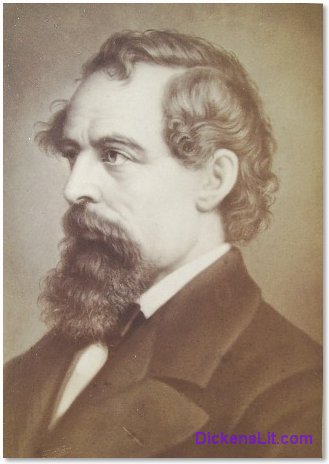

CHARLES DICKENS.

No novelist has dealt so directly with the home life of the world asCharles Dickens. He has painted few historic pictures; he has dealtmostly in interiors,—beautiful bits of home life, full of domesticfeeling. Indeed, we may say that his background is always the home, andhere he paints his portraits, often like those of Hogarth for strengthand grotesque effect. Here, too, he limns the scenes of hiscomedy-tragedy, and depicts the changing fashions of the time. The coloris sometimes a little crude, laid on occasionally with too coarse abrush; but the effect is always lifelike, and our interest in it isnever known to flag.

Nowhere else in all the range of literature have we such tenderdescription of home life and love, such intuitive knowledge of childlife, such wonderful sympathy with every form of domestic wrong andsuffering, such delicate appreciation of the shyest and most unobtrusiveof social virtues; nowhere else such indignation at any neglect ordesecration of the home, as in Mrs. Jellyby with her mission, in Mrs.Pardiggle with her charities, Mr. Pecksniff with his hypocrisy, and Mr.Dombey with his unfeeling selfishness. In short, Dickens ispre-eminently the prophet and the poet of the home.

Charles Dickens

Now, can it be possible that we must say of such a man as this, that inhis own life he was the opposite of all[Pg 336] that which he so feelinglydescribes,—that he desecrated the very home he so apostrophizes,—thathe put all his warmth, geniality, and tenderness into his books and keptfor his own fireside his sour humors and unhappy moods,—that he was"ill to live with," as Mrs. Carlyle puts it? We cannot believe it in sobald a form, but we are forced to admit that his married life seems tohave been in every way unhappy and unfortunate. No one could state thismore strongly than Dickens himself, in the letter he wrote at the timeof the separation. He said:—

"Mrs. Dickens and I have lived unhappily for many years. Hardly anyone who has known us intimately can fail to have known that we arein all respects of character and temperament wonderfully unsuitedto each other. I suppose that no two people, not vicious inthemselves, were ever joined together, who had greater difficultyin understanding one another, or who had less in common. Anattached woman-servant (more friend to both of us than servant),who lived with us sixteen years and had the closest familiarexperience of this unhappiness in London, in the country, inFrance, in Italy, wherever we have been, year after year, monthafter month, week after week, day after day, will bear testimony tothis. Nothing has on many occasions stood between us and aseparation but Mrs. Dickens's sister, Georgina Hogarth. From theage of fifteen, she has devoted herself to our home and ourchildren. She has been their playmate, nurse, instructress, friend,protectress, adviser, companion. In the manly consideration towardsMrs. Dickens, which I owe to my wife, I will only remark of herthat the peculiarity of her character has thrown all the childrenon some one else. I do not know, I cannot by any stretch of fancyimagine, what would have become of them but for this aunt, who hasgrown up with them, to whom they are devoted, and who hassacrificed the best part of her youth and life to them. She hasremonstrated, reasoned, suffered, and toiled, and come again toprevent a separation between Mrs. Dickens and me. Mrs. Dickens hasoften expressed to her her sense of her affectionate care anddevotion in the house,—never more strongly than within the lasttwelve months."

[Pg 337]

Again, in the public statement which he prepared for "Household Words,"alluding to a multitude of damaging rumors which were quickly put incirculation, he says:—

"By some means, arising out of wickedness or out of folly or out ofinconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble hasbeen made the occasion of misrepresentations most grossly false,most monstrous, and most cruel,—involving not only me, butinnocent persons dear to my heart, and innocent persons of whom Ihave no knowledge, if indeed they have any existence,—and sowidely spread that I doubt if one reader in a thousand will perusethese lines by whom some touch of the breath of these slandererswill not have passed like an unwholesome air.

"Those who know me and my nature need no assurance under my handthat such calumnies are as irreconcilable with me as they are intheir frantic incoherence with one another. But there is a greatmultitude who know me through my writings and who do not know meotherwise, and I cannot bear that one of them should be left indoubt or hazard of doubt through my poorly shrinking from takingthe unusual means to which I now resort of circulating the truth. Imost solemnly declare then—and this I do both in my own name andmy wife's name—that all lately whispered rumors touching thetrouble at which I have glanced are abominably false; and thatwhosoever repeats one of them, after this denial, will lie aswilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness tolie before heaven and earth."

This denial, coming from a man of truth and honor like Charles Dickens,must, once for all, dispose of that convenient way of accounting for thesad estrangement.

The reasons for the unhappy state of things were of a much morecomplicated nature than this. Only the most intimate of his friends everknew them in full, and of course they were debarred from making thempublic. But Professor Ward of Cambridge University, who has written avery kind and appreciative Life of Dickens, and one which gives a farmore pleasing idea of his character than the bulky and egotistical Lifeby Forster, gives a[Pg 338] clue to the whole trouble in the followingstatement. He says:—

"If he ever loved his wife with that affection before whichso-called incompatibilities of habits, temper, or disposition fadeinto nothingness, there is no indication of it in any of thenumerous letters addressed to her. Neither has it ever beenpretended that he strove in the direction of that resignation whichlove and duty made possible to David Copperfield, or even that heremained in every way master of himself, as many men have known howto remain, the story of whose wedded life and its disappointmentshas never been written in history or figured in fiction."

And this troublous condition of things was very much intensified byDickens having fallen violently in love with Mary Hogarth, Mrs.Dickens's youngest sister. This beautiful girl died at their house atthe early age of seventeen. No sorrow seems ever to have touched theheart and possessed the imagination of Charles Dickens like that for theloss of this dearly loved girl. "I can solemnly say," he wrote to hermother a few months after her death, "that waking or sleeping I havenever lost the recollection of our hard sorrow, and I never shall.""If," he writes in his diary at the beginning of a new year, "she waswith me now,—the same winning, happy, amiable companion, sympathizingwith all my thoughts and feelings more than any one I ever knew did orwill,—I think I should have nothing to wish but a continuance of suchhappiness." Throughout life her memory haunted him with great vividness.After her death he wrote: "I dreamed of her every night for many weeks,and always with a kind of quiet happiness, which became so pleasant tome that I never lay down without a hope of the vision returning." Theyear before he died he wrote to a friend: "She is so much in my thoughtsat all times, especially when I am successful, that the recollection ofher is an essential part of my being, and is as inseparable from myexistence as the beating of my heart is." In a word, she was the one[Pg 339]great imaginative passion of his life. He is said to have pictured herin Little Nell, and he writes after finishing that book, "Dear Mary diedyesterday when I think of it."

Have we not in this the key to all the sorrows of his domestic life?Could he have married the woman he loved in this manner, he woulddoubtless have been one of the tenderest and most devoted of husbands,and a family life as beautiful as any of the ideal ones he has depictedwould have resulted. It is probable that he did not know Mary Hogarthuntil after his marriage, when she came to live in his house, and whenhis youthful fancy for his wife had begun to decline. Miss Hogarth diedinstantly of heart-disease, without even a premonitory warning.

All accounts agree in calling Mrs. Dickens a very pretty, amiable, andwell-bred woman; and even if she was as infinitely incapable asrepresented, that alone would seem to be insufficient cause for soserious a trouble. Miss Georgina Hogarth, whom all describe as a verylovely and superior person, possessed the executive ability Mrs. Dickenslacked, it would seem; for all visitors both to Tavistock House andGad's Hill describe with enthusiasm the perfect order which prevailed inthe large establishments, attributing this in part at least to Dickens'sown intense love of method and passion for neatness. But no man withoutthe aid of feminine head and hands would have succeeded in attaining tothis perfect housekeeping, especially where the family consisted of ninechildren, as in this case.

Hans Christian Andersen thus describes a visit to Gad's Hill:—

"It was a fine new house, with red walls and four bow-windows, anda jutting entrance supported by pillars; in the gable a largewindow. A dense hedge of cherry-laurel surrounded the house, infront of which extended a neat lawn, and on the opposite side rosetwo mighty cedars of Lebanon, whose crooked branches spread theirgreen far over[Pg 340] another large lawn surrounded by ivy and wildvines, the hedge being so dense and dark that no sunbeam couldpenetrate it.

"As soon as I stepped into the house, Dickens came to meet mekindly and cordially. He was now in the prime of life, still soyouthful, so active, so eloquent, so rich in the most pleasanthumor, through which his sterling kind-heartedness always beamedforth. As he stood before me in the first hour, so he was andremained during all the weeks I passed in his company,—merry,good-natured, and full of charming sympathy. Dickens at home seemsto be perpetually jolly, and enters into the interests of gameswith all the ardor of a boy. My bedroom was the perfection of asleeping-apartment; the view across the Kentish hills, with adistant peep of the Thames, charming. In every room I found a tablecovered with writing-materials, headed notepaper, envelopes, cutquill-pens, wax, matches, sealing-wax, and all scrupulously neatand orderly. There are magnificent specimens of Newfoundland dogson the grounds, such animals as Landseer would love to paint. Oneof these, named Bumble, seems to be a favorite with Dickens."

Mr. Mackenzie writes:—

"Eminently social and domestic, he exercised a liberal hospitality,and though he lived well as his means allowed, avoided excesses. Itis said of him that he never lost a friend, never made an enemy."

From all sources comes the same report of his geniality, of his devotionto his children and their devotion to him, of his constant generosityand good-humor. Byron's old servant said that Lady Byron was the onlywoman he ever saw who could not manage his master. Was this also true ofMrs. Dickens? Was she the only one who found him "ill to live with"? Itmay be; and yet one can easily imagine him to have been a man of moods,and that in some of these moods it would be best to give him a wideberth. The very excess of his animal spirits may have been wearying toone who could not share them; and that he was egotistical to a degree,and vain, and fond of[Pg 341] flattery, goes without saying. A lady in the"English-woman's Magazine" tells this story of his wild and recklessfun, and it is matched by many others. They were down on the seashore inthe moonlight, and had been dancing there.

"We then strolled farther down to watch the fading light. The tidecame rippling in. The night grew darker,—starless, moonless.Dickens seemed suddenly to be possessed with the spirit ofmischief; he threw his arm around me, and ran me down the inclinedplane to the end of the jetty till we reached the toll-post. He puthis other arm around this, and exclaimed in theatrical tones thathe intended to hold me there till the sad sea waves should submergeus. 'Think of the sensation we shall create.' Here I implored himto let me go, and struggled hard to release myself. 'Let your minddwell upon the column in the "Times" wherein will be vividlydescribed the pathetic fate of the lovely E. P., drowned by Dickensin a fit of dementia. Don't struggle, poor little bird; you arehelpless.' By this time the last gleam of light had faded out, andthe water close to us looked uncomfortably black. The tide wascoming up rapidly, and surged over my feet. I gave a loud shriek,and tried to bring him back to common-sense by reminding him thatmy dress—my best dress, my only silk dress—would be ruined. Eventhis climax did not soften him; he still went on with hisserio-comic nonsense, shaking with laughter all the time, andpanting with his struggles to hold me. 'Mrs. Dickens,' I shrieked,'help me! Make Mr. Dickens let me go—the waves are up to myknees.' 'Charles,' cried Mrs. Dickens, 'how can you be so silly?You will both be carried off by the tide!' And it was not until mydress had been completely ruined that I succeeded in wrestingmyself from him. Upon two other occasions he seized me and ran withme under the cataract, and held me there until I was thoroughlybaptized and my bonnets a wreck of lace and feathers."

The same writer says,—and she is one who writes from familiar personalacquaintance,—"To describe Dickens as always amiable, always just, andalways in the right, would be simply false and untrue to Nature;" and[Pg 342]she relates several anecdotes going to prove that he was sometimescapricious, not always responsive to appeals for help, and other thingsof that sort; all of which may be true and not be very damaging. Thiswriter tells still another story of his reckless fun-making, asfollows:—

"We were about to make an excursion to Pegwell Bay, and lunchthere. Presently Dickens came in in high glee, flourishing about ayard of ballads, which he had bought from a beggar in the street.'Look here,' he cried exultingly, 'all for a penny. One song aloneis worth a Jew's eye,—quite new and original, the subject beingthe interesting announcement by our gracious Queen.' He commencedto give us a specimen, but after hearing one verse there arose acry of universal execration. He pretended to be vexed at our'shutting him up.' said there was nothing wrong in it, he hadwritten a great deal worse himself; and when we were going to enterthe carriages he said: 'Now, look here! I give due notice to alland sundry, that I mean to sing that song, and a good many others,during the ride; so those ladies who think them vulgar can go inthe other carriages. I am not going to invest my hard-earned pennyfor nothing.' I was quite certain that Charles Dickens was the lastman in the world to shock the modesty of any female, and too muchof a gentleman to do anything that was annoying to us, but Ithought it as well to go in the other carriage; and so he had noladies with him but his wife and Mrs. S——. I was not sorry,however, to be where I was, as I heard for the next half-hourportions of those songs wafted on the breeze; and the bursts oflaughter from ladies and gentlemen and the mischievous twinkle inDickens's eye proved that he was in such a madcap mood that it wasas well there were none but married people with him,—the subjectbeing of a 'Gampish' nature. But he was not always full of spiritsor even-tempered,—indeed, I was sometimes puzzled by thevariability of his moods."

Anecdotes like the following, told by Blanchard Jerrold, abound in allwriters who wrote of Dickens from personal knowledge:[Pg 343]—

"A very dear friend of mine, and of many others to whom literatureis a staff, had died. To say that his family had claims uponDickens is to say that they were promptly acknowledged andsatisfied, with the grace and heartiness which double the gift,sweeten the bread, and warm the wine. I asked a connection of ourdead friend whether he had seen the poor wife and children. 'Seenthem?' he answered. 'I was there to-day. They are removed into acharming cottage. They have everything about them; and just thinkof this: when I burst into the room, in my eager survey of the newhome, I saw a man in his shirt-sleeves up some steps, hammeringaway lustily. He turned. It was Charles Dickens, and he was hangingthe pictures for the widow. . . . Dickens was the soul of truth andmanliness as well as kindness, so that such a service as this cameas naturally to him as help from his purse.'"

Jerrold continues:—

"There was that boy-element in him which has been so often remarkedof men of genius. 'Why, we played a game of knock 'em down only aweek ago,' a friend remarked to me last June, with beaming eyes,'and he showed all the old astonishing energy and delight in takingaim at Aunt Sally.' My own earliest recollections of Dickens are ofhis gayest moods, when the boy in him was exuberant, and leap-frogand rounders were not sports too young for the player who hadwritten 'Pickwick' twenty years before. The sweet and holy lessonswhich he presented to humanity out of the humble places in theworld could not have been evolved out of a nature less true andsympathetic than his. It wanted such a man as Dickens was in hislife to be such a writer as he was for the world."

One more anecdote. J. C. Young tells us that one day Mrs. Henry Siddons,a neighbor and intimate of Lord Jeffrey, who often entered his libraryunannounced, opened the door very gently to see if he were there, andsaw enough at a glance to convince her that the visit was ill-timed. Thehard critic of the "Edinburgh Review" was sitting in his chair with hishead on the table in deep grief. As Mrs. Siddons was retiring, in thehope that her[Pg 344] entrance had been unnoticed, Jeffrey raised his head andkindly beckoned her back. Perceiving that his cheek was flushed and hiseyes suffused with tears, she begged permission to withdraw. When hefound that she was intending to leave him, he rose from his chair, tookher by both hands, and led her to a seat.

"Don't go, my dear friend; I shall be right again in another minute."

"I had no idea you had had any bad news, or cause for grief, or I wouldnot have come. Is any one dead?"

"Yes, indeed. I'm a great goose to have given way so; but I could nothelp it. You'll be sorry to hear that little Nelly, Boz's little Nelly,is dead."

Dear, sweet, loving little Nell! We doubt if any other creation of poetor novelist in any language has received the tribute of as many tears asthou. From high, from low, on land, on sea, wherever thy story has beenread, there has been paid the spontaneous tribute of tears. Whether ornot many of the fantastic creations of the great master's hand will livein the far future we cannot tell, but of thy immortality there is nomore question than there is of that of Hamlet or of Lear. Bret Hartetells us of a camp among the stern Sierras, where a group of wanderersgathered about the fire, and one of them arose, and "from his pack'sscant treasure" drew forth the magic book; and soon all their own wantsand labors were forgotten, and

"The whole camp with Nell on English meadows

Wandered and lost their way."

And from many different sources come stories of her influence upon thehearts and minds of all classes and conditions of men.

Of Dickens's personal appearance and of the leading traits of hischaracter much has been written, and by some of the keenest observers ofhis time. He is said to have been a very small and sickly boy, subjectto attacks of violent spasm. Although so fond of games and sports[Pg 345] whena man, as a boy he evinced little interest in them, probably on accountof his ill health. We should naturally think of him as the autocrat ofthe playground, and the champion in all games of strength and skill; butsuch was not the fact. He was extremely fond of reading, at a very earlyage, and of acting little plays, and showing pictures in a magiclantern; he even sang at this time, and was as fond of fun as in laterlife. When quite young he and his companions mounted a small theatre,and got together scenery to illustrate "The Miller and his Men," and oneor two other plays.

Mr. Forster describes him thus:—

"The features were very good. He had a capital forehead, a firmnose, with full, wide nostril, eyes wonderfully beaming withintellect and running over with humor and cheerfulness, and arather prominent mouth, strongly marked with sensibility. The headwas altogether well-formed and symmetrical, and the air andcarriage of it extremely spirited. The hair, so scant and grizzledin later days, was then of a rich brown and the most luxuriantabundance, and the bearded face of the last two decades had hardlya vestige of hair or whisker, but there was that in the face, as Ifirst recollect it, which no time could change, and which remainedimplanted on it unalterably to the last. This was the quickness,keenness, and practical power, the eager, restless, energetic lookon each several feature, that seemed to tell so little of a studentor writer of books, and so much of a man of action and business inthe world. Light and motion flashed from every part of it."

Another keen observer writes:—

"The French painter's remark that 'he was more like one of the oldDutch admirals we see in picture galleries than a man of letters,'conveyed an admirably true idea to his friends. He had, indeed,much of the quiet, resolute manner of command of a captain of aship. He trod along briskly as he walked; as he listened, hissearching eye rested on you, and the nerves in his face quivered,much like those in the delicately formed nostrils of a finely breddog. There was a curl or two in his hair at each side, which wascharac[Pg 346]teristic; and the jaunty way he wore his little morning hat,rather on one side, added to the effect. But when there wasanything droll suggested, a delightful sparkle of lurking humorbegan to kindle and spread to his mouth, so that, even before heuttered anything, you felt that something irresistibly droll was athand."

Mr. Mackenzie tells us:—

"Dickens's personal taste in dress was always 'loud.' He loved gayvests, glittering jewelry, showy satin stocks, and everythingrather prononcÚ; yet no man had a keener or more unsparingcritical eye for these vulgarities in others. He once gave to afriend a vest of gorgeous shawl pattern. Soon after, at a party, hequizzed his friend most unmercifully for his stunning vest,although he had on him at that very moment its twin brother orsister, whichever sex vests belong to."

There was an almost morbid restlessness in the man, out of which arosehis habit of excessive walking. When he was writing one of his greatbooks he could not be away from London streets, and he used to walkabout in them at night for hours at a time, until his body wascompletely exhausted; in this way only could he get sleep. When notcomposing he loved long country walks, and probably injured his healthmuch in later life by the great length of these tramps across country.His restlessness showed itself also in many other ways. The element ofrepose was not in him. "My last special feat," he writes once whenunable to sleep, "was turning out of bed at two, after a hard day,pedestrian and otherwise, and walking thirty miles into the country tobreakfast."

The story is told, too, of a night spent in private theatricals,following a very laborious day for Dickens, and of his being so muchfresher than any of his companions that towards morning he jumpedleap-frog over the backs of the whole weary company, and was not willingto go to bed even then. His animal spirits were really inexhaustible,and this was the great unfailing charm of his companionship. He neverdrooped or lagged, but was always alert,[Pg 347] keen, and ready for anyemergency. Out-of-door games he entered into with great hilarity, andwas usually the youngest man in the party. There was a positive sparkleand atmosphere of holiday sunshine about him, and to no man was the word"genial" ever more appropriately applied.

He carried an atmosphere of good cheer with him in person as he did inhis books, and was fond of the sentiment of joviality; wrote, indeed, agreat deal about feasting, but was really abstemious himself, though heliked to brew punch and have little midnight suppers with his friends.Yet at these same suppers he ate and drank almost nothing, though hefurnished the hilarity for the whole party.

His powers of microscopic observation have seldom been equalled. AsArthur Helps said of him, he seemed to see and observe nine facts whilehis companion was seeing the tenth. His books are full of the results ofthis accurate observation. Comparatively little in them is invention;the major part of everything is description of something he has seen andnoted. When he was engaged in reporting, among eighty or ninetyreporters, he occupied the very highest rank, not merely for accuracy inobserving, but for marvellous quickness in transcribing. His wonderfulability as an actor is known to all. Probably he would have been thegreatest comedian of his day if he had not been one of its greatestwriters. His love for the theatre was an absorbing passion. He was quiteas good a manager as actor, and could bring order out of the chaos ofrehearsals for private theatricals, as no other man has ever been knownto do. Carlyle, who was one of the keenest observers of men our time hasproduced, said: "Dickens's essential faculty, I often say, is that of afirst-rate play-actor." Macready also gave it as his opinion thatDickens was the only amateur with any pretensions to talent that he hadever seen.

Among the weaknesses of his character were his love of display, whichamounted to ostentation sometimes; his[Pg 348] fear of being slighted; hisvanity, which was prodigious, and a certain hardness, which at timesamounted to aggressiveness and almost to fierceness. The displays ofthis latter quality were very rare; but they left an ineffaceableimpression upon all witnesses.

The only political questions which deeply moved him were those socialproblems to which his sympathy for the poor had always directed hisattention,—the Poor Law, temperance, Sunday observance, punishment andprisons, labor and strikes. But that he much influenced the legislationof his country by his writings, no man can doubt. In religion he was aLiberal. Born in the Church of England, we are told by Professor Wardthat he had so strong an aversion for what seemed dogmatism of any kind,that for a time—in 1843—he connected himself with a Unitariancongregation, and to Unitarian views his own probably continued duringhis life most nearly to approach.

In his will he says:—

"I commit my soul to the mercy of God through our Lord and SaviourJesus Christ, and I exhort my dear children humbly to try to guidethemselves by the teaching of the New Testament, in its broadspirit, and to put no faith in any man's narrow construction of itsletter here or there."

Although a man of deep emotional nature, his religion was, after all,mostly a religion of good deeds. Helpfulness, kindliness,—these were tohim the supreme things. One who knew him well wrote after his death:—

"I frankly confess that having met innumerable men and had dealingswith innumerable men, I never met one with an approach to hisgenuine, unaffected, unchanging kindness, or one that ever found sosunshiny a pleasure in doing one a kindness. I cannot call to mindthat any request I ever made to him was ungranted, or left withoutan attempt to grant it."

Upon this point all who ever knew the man are well[Pg 349] agreed. It willsuffice. To him who loved so much, if need be much will be forgiven.

As we close this paper, how softly pass before us the long procession ofthe men and women he has created,—for they all seem thus to us,—notcharacters, but people, many of them personal acquaintances of our own.There are actual tears in our eyes as the little company of childrenpass in review, led by David Copperfield, and followed by Oliver Twist,with Paul Dombey in his wake, and little Nell timidly pressing near;while trooping after, sad, tearful, or grotesque, come Florence Dombey,poor Joe, Pip and Smike, Sloppy and Peepy, Little Dorrit and Tiny Tim,and many more of those with whose sorrows we have sympathized, and overeach and all of whom we have wept hot tears in the days that are nomore. Dream-children, he calls them; but the great world acknowledgesthem as real beings, and sorrows and rejoices with them, even more, itis to be feared, than it does sometimes with the children of flesh andblood, homeless and forsaken as many of them are. But for the sake ofTiny Tim many an old Scrooge has softened his hard heart somewhat; andin memory of poor Joe many a hardened city man has been a little lessimperious to the beggar-boy about "moving on." Even poor Smike hasserved the purpose of ameliorating a trifle the hard lot of suchunfortunates as he, who are tyrannized over in public institutions; and,altogether, Dickens's dream-children can be said to have been useful intheir day and generation.

How the other old friends come following on! We have our own peculiargreeting for each. We cannot help holding our sides as Mr. Pickwick andSam Weller go by, followed by Captain Cuttle with his hook, the finestgentleman of them all; by the Major and Mrs. Bagnet, by whom disciplineis maintained in the group; by Micawber, with his large outlines andflowing periods; and by Mrs. Micawber and her relations, senselessimbeciles or unmitigated scoundrels all, as her husband testifies; byMrs. Gamp, by Barkis, and even the young man[Pg 350] by the name of Guppy. Asmile spreads over the face of the whole reading world at the baremention of their names. How the smiles deepen into tears as we thinkover the other friends to whom he has introduced us,—mutual friends ofus all; of whom we talk when we congregate together, with just as muchof real feeling and interest as we do of other friends of flesh andblood, laugh over their foibles and follies, pity their sorrows, blametheir acts, and all with no other feeling than that of utter reality.

Will little Nell's friend, the old schoolmaster, ever cease to drawtears from our eyes? Shall we ever weary of gentle Tom Pinch? Shall wenot always touch our hats to Joe Gargery? Shall we ever cease loving Mr.Jarndyce, even when the wind is in the east? And will Agnes and Estherever pall upon our taste? Not, we verily believe, until the sources offeeling are dried up in us forever, and we have grown indifferent to allof earth. What an array of them there are, too! The bare catalogue oftheir names would fill a volume, and it would not be bad reading to thegenuine Dickens lover,—recalling, as each name would, so much of vividportrayal, and starting so many associations in the mind. But there isno need to repeat the names; the big, dull old world long ago learnedthem by heart. Nor will they soon be relegated to the shades. While thetide of English speech flows on, they will linger, component parts ofthe language itself.